Two Newlyweds dance to the sounds of a Violinist during a wedding from the time of the renaissance.

There were several factors influencing the music that was being performed for weddings in England during the mid to late 1500s and early 1600s. The first major influences were the Protestant Reformation and Puritanical beliefs. Another driving force was the newly emerging educated middle class and its quest to follow the fashions of nobility. All the while newly invented musical instruments were improving sound quality and versatility allowing for more complicated and intricate instrumental music. These conditions set the stage for music to manifest itself in every walk of life during the Renaissance. Therefore, music was certainly an important element for a memorable Renaissance wedding.

By the Reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the church had become an important part of any marriage. In fact, for a marriage to be legal, the pending union needed to be announced in church on three consecutive Sundays. It is important to understand, though, that in England the church was in a tremendous period of transition. This was a result of Henry VIII’s excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church and his subsequent creation of the Anglican Church. When Queen Elizabeth I rose to power she made a concerted effort to maintain peace in the potentially volatile struggles between Catholics and Protestants. As a result, a group of highly educated Protestants became extremely critical of the Queen’s religious compromises. This group became known as Puritans because they wanted to purify the Anglican Church of Catholicism. Since Marriage was so intrinsically tied to the church, the Puritan’s religious principles managed to manifest itself into most aspects of wedding music.

Once the intention to marry was made public in church through Crying the Banns it was possible to hold a wedding ceremony. Then as now, the first part of a wedding ceremony was the procession. In the time of Renaissance England the procession was a noisy and raucous affair. It began at the bride’s house where the bride would prepare for the ceremony with her bridesmaids. The groom and his family would often meet at the bride’s home and commence the procession following the bride’s family. The procession would then travel to the local church accompanied by musicians who performed on flutes, viols, drums and other “haut” (loud) instruments. Through the first half of the 16th century Bagpipes were also used in processionals and there is documentation of ministers performing on them during the procession. However, by the end of the century the popularity of bagpipes had waned significantly. There are records that indicate that the Puritans objected to the processionals and even brought the matter before Parliament.

The procession would eventually arrive at a Christian worship service that was quite a bit different compared with the customs of today. One of the most noticeable differences would have been the lack of seating. There were no pews, and the congregation stood for the duration of the service.

The Renaissance wedding ceremony was a very solemn service. There would have been little to no music performed during most ceremonies. If music was performed it would have most likely been Madrigal or vocal. The sparse presence of music resulted from the Puritan’s believe that most of the traditional religious music should be discarded. This was largely because the Anglican Church service was to be held entirely in English as opposed to Latin. Unfortunately this has resulted in a great deal of early English sacred music performed in Latin being lost to the sands of time.

The Puritans were also quite vocal about the style of music used in religious services especially when it regarded Polyphony and instrumentation. Polyphony is music with two or more independent melodic parts sounded together. This counterpoint had become the mainstream in music throughout Europe during the Renaissance. The Puritans believed that the gospel sung in polyphony interfered with the congregation’s ability to comprehend the word of God. The Puritans also believed that the use of musical instruments during a church service was an element of Popery. They deemed instrumental music in worship services to be profane leaving the worshipers more interested in the musical performance than in the word of God. This mindset resulted in the removal of 100s of organs from churches by the over zealous reformers throughout England and much of the rest of reformed Europe. Interestingly, though, many smaller organs created by the same craftsman who had previously built instruments for churches began appearing in private homes.

During the Renaissance the chief benefactor to the arts was the Church. Unfortunately, the Puritans pious and hard-nosed stance on sacred music created a great void in the labor market for instrumental musicians. Many of the most talented musicians were forced to work abroad or even gave up the trade entirely. The performers that managed to scrape by found work performing in weddings for wealthy and middle class families with enough status to ignore the Puritan’s creeds. A select few musicians were lucky, or perhaps talented enough to gain patronage from the extremely wealthy nobility in private chapels. One example of a private house of worship was Queen Elizabeth’s own Chapel Royal. Chapel Royal was the primary venue for several famed Elizabethan era composers including William Byrd.

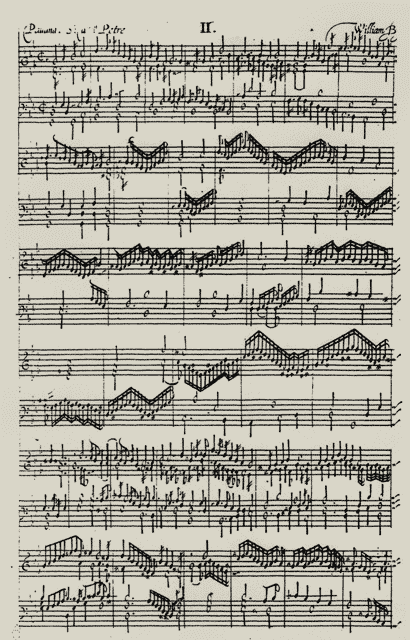

William Byrd became one of the most renowned composers of the renaissance in England and specialized in music utilizing polyphony. Some of Byrd’s Hymns are still favorites of the Anglican Church today. Although it is unclear whether any of Byrd’s work was actually performed during weddings of the Elizabethan Era, some of his compositions used subject matter directly related to marriage. Two prime examples The Match That’s Made and La Verginella were contained in his 1588 volume Psalms, Sonnets & Songs of Sadness and Piety.

Eight pieces for Virginal by William Byrd were also published in Parthenia, a wedding gift for Elizabeth Stuart who was the daughter of King James I. Parthenia was published between 1611 and 1613 and has the added distinction of being the first published collection of English keyboard music.

There may have been little or no music performed during Renaissance wedding ceremonies, however, melody filled the air during wedding feasts. The music performed at a feast would have varied widely depending on the social class of the newlyweds.

The newly emerging middle class had an extremely strong appreciation of music. Most nobleman and merchants were able to read pricksong or sheet music. In lieu of video games and television, Elizabethan families would sing and play instruments following dinner in their newly found leisure time. Lutes were by far the most popular instrument and at least one could be found in most middle and upper class homes. Music was so important that if it was found that a dinner guest could not sing pricksong at sight, (sight read) he would be looked at in disdain in many circles and considered to be of unsavory character. With an appreciative audience like this it is easy to understand the importance there would have been in hiring the best professional musicians during a wedding feast.

Any wedding feast, regardless of class, would have included dancing. Dance was a popular form of social exercise. Queen Elizabeth herself would dance every morning. During the English Renaissance dances would be set to a variety of instrumentation including a cappella, instrumental or a combination of both. The Dancers would follow the periods “pop” music, which tended to be Broadside Ballads. One of the period’s most popular broadside dances was called Turkeylony. The following lyrics were printed in 1557 or 1558 and are believed to have been sung along with the Turkeylony melody.

If ever I marry, I’ll marry a maid

To marry a widow I’m sorely afraid;

For maids they are simple, and never will grutch, (grudge)

But widows full oft, as they say, know too much

The dances at wedding feasts for all classes would have most likely been stepped in circles or in rows that could support an unlimited number of participants. However, There were other popular dances of the time that included a fixed number of dancers such as two or three couples.

Although the upper and middle classes did partake in the dances of the commoners, they also had a long list of specialized dances known as Court Dances. Court Dances could be divided into two categories basse which were slower dances or Haute or fast dances. A dance party during the Elizabethan Renaissance would begin with basse dances. Basse Dances were considered “low” dances because the dancers would stay on the ground. As the wedding feast progressed, the music’s tempo would increase to tempos suitable for haute dances. Haute Dances were considered “high” because the dancers would actually skip, hop and jump during them.

The slower basse dances included the Allemagne which was considered the most sentimental court dance, and would have certainly been suitable as the first dance for a pair of newlyweds. The couples partaking in Allemagne or Alman held each others hands through the entire dance. The beauty of this dance didn’t come from fancy steps and flourishes, but rather from its grace and tenderness.

At a racier wedding, the married couple might dance a Lavolta, which were written for two people. This haute waltz was one of the most difficult dances because men would lift their dance partner into the air. The leap often caused the lady’s skirt to lift. In some circles this would be far too obscene. The more conservative members of the court were dismayed that a lady’s knees would be shown and in some cases their garter would be revealed. A Fashionable woman who planned to dance the Lavolta would be sure to pick a garter that was adorned with gold or silver. Onlookers would laugh as the newlywed’s grasped and bumped parts of the anatomy that were considered taboo by most. The groom would place his right hand on the bride’s back and his left hand just under her bosom. The groom would then use his thigh to push the bride’s hindquarters further into the air as she twirled. Many preachers and Puritans condemned the Lavolta because it could lead to much debauchery, and at a wedding feast this would certainly be the case.

The peasant or servant class during the time of the Renaissance also was very fond of dancing. There isn’t a great deal known about the daily lives of the peasant class, however, their dances eventually became popular with the nobility as well. As a result there is a fair amount of documentation regarding the peasant “country dances.” Some of the dances that found their way into noble society included Brawls, Gavottes, Jigs, hornpipes and reels.

Many of the peasant wedding customs were passed down from pagan traditions. One key example of this would be Morris Dance. Morris Dances were especially associated with May Day or May 1st, but they were also common at country wedding feasts. The May Day celebration originated in England as far back as the time of the Druids. The tradition continued with the Roman occupation of England as it became a time of praise for the God of Spring, Flora. The May Day tradition had further evolved by the time of the renaissance due to many centuries of European conflation and conflict. As a result a new set of characters was associated with Morris dance. They included the Queen or Lady of May, a Jester, A Piper, and up to six Morris Dancers.

The Piper in a Morris Dance would have most likely been a Pipe and Tabor player. The pipe and tabor was perhaps the earliest version of the “one man band.” The “pipe” in this case was a home made three holed whistle or flute played using the thumb, index and middle fingers. While the performer blew away on the pipe, he would pound out a lively beat using a stick on a drum slung over his shoulder called a tabor. It also wasn’t uncommon for other percussionists, fiddlers, harpists and bagpipers to perform during Morris Dances. Although still popular in the lower class during the time of Elizabeth I, the pipe and tabor was quickly being replaced by more modern woodwind instruments in more affluent circles.

Harmonious Music actually still regularly includes a Morris Dance in their wedding ceremony set. The name of the tune is English Country Gardens. Although the ensemble does not include vocals for the performance they are as follows:

How many kinds of sweet flowers grow

In an English country garden?

We’ll tell you now of some that we know

Those we miss you’ll surely pardon

Daffodils, heart’s ease and phlox

Meadowsweet and lady smocks

Gentian, lupin and tall hollyhocks

Roses, foxgloves, snowdrops, forget-me-nots

In an English country garden

How many insects come here and go

In an English country garden?

We’ll tell you now of some that we know

Those we miss you’ll surely pardon

Fireflies, moths and bees

Spiders climbing in the trees

Butterflies drift in the gentle breeze

There are snakes, ants that sting

And other creeping things

In an English country garden

How many songbirds fly to and fro

In an English country garden?

We’ll tell you now of some that we know

Those we miss you’ll surely pardon

Bobolink, cuckoo and quail

Tanager and cardinal

Bluebird, lark, thrush and nightingale

There is joy in the spring

When the birds begin to sing

In an English country garden

Other variations of Morris Dances would include the use of a “Hobby Horse.” A Hobby Horse was a man wearing a wicker frame in the shape of a horse. He would prance around and mimic the movements of an actual horse. In some versions another person would wear a similar costume intended to resemble a dragon. The Hobby Horse Knight would then slay the Dragon reenacting the story of St. George.

The Morris Dancing at spring wedding feasts took place around the May Pole. The May Pole was another relic of England’s pagan past and most likely originated in Germany. It was a large tree of varying sizes sunk into the ground. This giant post would be painted and adorned with flowers and wreathes. The May Pole was considered a phallic symbol, and dancing around it was actually a fertility right. Visitors to modern renaissance fairs will watch dancers weave ribbons around the May Pole. However, this tradition did not start until the 19th century as England reexamined its “Merry-Old” past. Puritans despised the May Pole believing May Pole dancing to be a form of idol worship. As a result, it was banned in England by the Mid-Sixteen hundreds.

Conclusion

Although, the customs were somewhat different, there are still many parallels between music that was performed in religious and wedding ceremonies from the Reign of Queen Elizabeth I and the contemporary United States. Currently, as houses of worship struggle to maintain membership many are stripping away the more traditional music in favor of more contemporary sounds. However, customs and traditions still remain varied in the United States, often depending on socio-economic conditions and religious and cultural differences. Meanwhile, the innovations of electricity and the resulting modern instruments such as electric guitars and MIDI keyboards continue to push the use of music in wedding ceremonies to new heights.

Sources

Music from the Age of Shakespeare: A Cultural History

by Suzanne Lord

William Byrd’s Fall From Grace and his First Solo Publication of 1588: A Shostakovian “Response to Just Criticism”?

By Jeremy L. Smith

William Byrd: The Collected Works of William Byrd.

Edited by Edmund. H. Fellowes

http://www.elizabethan.org/compendium/62.html

http://celyn.drizzlehosting.com/mrwp/mrwed.html

http://www.archive.org/stream/popularmusicofol01chapuoft/popularmusicofol01chapuoft_djvu.txt

http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/lod/vol2/ecd_16th.html

http://www.hago.org.uk/free/country-garden/lyrics/

The lute in Britain: a history of the instrument and its music

By Matthew Spring

Courtly Dance of the Renaissance: A New Translation and Edition of the Nobilitá di Dame (1600)

By Fabrito Caroso, Julia Sutton, F. Marian Walker

The Lute Books of Ballet and Dallis Music and Letters Journal

by H. Macaulay FitzGibbon

Popular Music of the Olden Time Vol. 1

by William Chappell

Shakespeare’s Songbook Vol. 1

by Ross W. Duffin

Tags: Allemagne, bagpipes, Basse, Brawls, ceremony, Christian, Crying the Banns, Dance, Drums, Elizabethan, English, English Country Gardens, Feast, garter, Gavottes, Haut, Haute, hornpipes, instrumental, Jigs, King James I, Latin, Lavolta, Lute, madrigal, May Pole, Morris Dance, music, musicians, organs, Parthenia, Pipe and Tabor, Polyphony, Pricksong, procession, Protestant Reformation, Psalms, Puritan, Queen Elizabeth, reels, Renaissance, Sonnets & Songs of Sadness and Piety, The Match That’s Made, Turkeylony, Viol, wedding, William Ballet, William Byrd

Posted in General Music History, Uncategorized, Wedding Music