Written and Illustrated by Eric Ortner for The Civil War Courier in 1999

Music was an important part of the Civil War. It called the beginning and end of the day, and was a means for the commander to communicate with his troops in a heated battle. As well as a substantial communication tool, it was also a way for soldiers to overcome the boredom, and drudgery of everyday life. The sounds of a powerful marching band could lift the morale of one’s regiment or even frighten an opposing army. Robert E. Lee said at the onset of the war, “I don’t believe we can have an army without music.”

A wind band composed entirely of brass instruments quickly became the favorite and most practical form of an ensemble in America. However, the brass band was not originally an American idea. In 1836, the Bradley Old Reed Band performed an entertainment in Woodhouse Moore to honor the coronation of William IV. At this time the ensemble had a mixture of brass and woodwind instruments. A few days later the musicians in Bradley’s ensemble made the decision to do away with the woodwinds. With this decision they became the first brass band in history. Still extreme patriotism prior to the War Between the States along with the war itself pushed this new style of ensemble to greater heights.

The new brass band was made possible as a result of some great new technology relating to brass instruments. This included improvements in mining and refining the elements required to create brass. Another significant advancement in technology dates back to 1810 with the invention of the keyed bugle. Once again it was an Englishman who was responsible for this advancement. Joseph Halliday, who was the bandmaster of the Cavan Militia, cut tone holes into the common military bugle. Mr. Halliday then added woodwind like keys to cover the holes. The instrument that Halliday modified was half-moon shaped and called a Hanoverian Bugle. By 1814 the Hanoverian Bugle was the symbol of the English Light Infantry.

The advancement of the keyed bugle was significant because until its invention, brass instruments were very confined in terms of pitch and range. One such limited instrument was called the Natural Trumpet. The musician performing on these natural trumpets was confined to only a few of the twelve notes in western music theory. They were octaves, fifths, fourths, major thirds and minor thirds. These are the natural overtones in music, and all natural trumpets, no matter what their tuning, were limited to them.

The fundamental principle of all brass instruments, which started with natural trumpets, requires the performer to tighten the tension of the lips on the mouthpiece. This causes the variation in pitch. With this in mind, musicians in a section would specialize in mastering a specific range of notes.

The keyed bugle was a welcome improvement because it allowed the player to more easily achieve an entire chromatic series of notes. The keyed bugle’s keys were similar to that of a clarinet or modern day saxophone. The sound of these instruments can be described as mellow. This results from the acoustical phenomena associated with its vented (keyed) design, and from the instruments conical shape.

In brass instruments, there are generally two different shapes. The first is conical or cone shaped which represents the bugle family. The bore of the tubing in conical brass instruments continuously widens as it moves from the mouthpiece to the bell of the instrument. The other basic design of brass instruments is cylindrical. Trumpets are members of this family. The diameter of the tubing in a cylindrical instrument stays the same width all the way from the mouthpiece to the bell. This results in a much more brilliant sound than the conical style.

In the conical style, the keyed bugle is strongly linked to the cornet a pistons and was eventually replaced in popularity and functionality by this instrument. The keyed bugle’s major flaw was that over blowing could change its intonation. The invention of the valve changed all of that.

Despite the success of the keyed bugle, by 1839 most Europeans had embraced the improvements to brass instruments that used valves. Thus, the prominence of the keyed bugle in both civilian and military bands in Europe began to wane. This had a little to do with the economic interests of the band leaders. That is because brass band leaders were often partners with instrument manufacturers. Therefore, when they took over an ensemble, it was in the leader’s financial interest to purchase their own company’s instruments and replace the existing ones. Although greed definitely did play into the leader’s decision, it was important to have a complete set of matching instruments. Every band leader had his own personal favorite. At this time there was no uniform tuning from manufacturer to manufacturer. Thus with a new leader and orchestration came the need for a complete set of 17 new instruments. Most brass bands in the mid 1800s had between 17 and 24 members. The valve for brass instruments is said to have been invented by two Berliner, Heinrich Stolzel, and Freiderch Bluhmel. They patented their design in 1818. However, the invention was further refined by the French in 1825, and in 1829, the cornet a pistons was used in Paris for Rossini’s Guillaume Tell and this instrument quickly grew in popularity.

The 1830s saw numerous improvements to valve designs. Some of the more successful and long-lasting adaptations were the invention of the Vienna Twin-Piston valve patented by Leopold Uhlman in 1830; the Rad-Maschine, a rotary-action valve designed by Joseph Riedl and patented in 1832; the Berliner Pumpen Valve, a piston valve designed by Wilhelm Wieprecht and J.G. Moritz in Prussia 1835; and the Perinet Valve which earned its name in 1839 from its Parisian inventor.

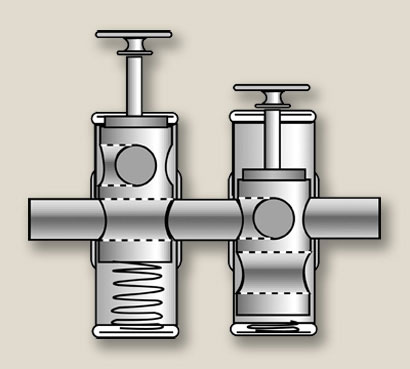

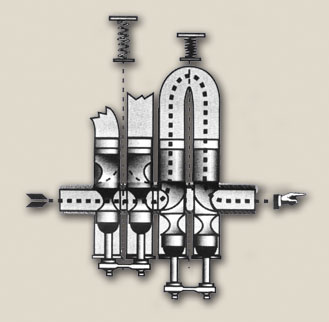

Valve mechanisms can be grouped into two basic types; these are piston and rotary valves. Piston Valves have buttons which can be pressed down. They are easily associated with the modern day trumpet. When the button of piston valve is pressed, it reroutes the airflow through the pathway of additional tubing. It does this by sealing the main tube in an up and down motion forcing the airflow into the secondary tube which is inaccessible by the airflow otherwise. Once the air completes this long-cut, it is permitted to reenter the main tube. This creates a lower pitch by lengthening the tubing.

A rotary valve operates by a key or lever. When the performer presses this key a string, mechanical linkage or both (as is the case today), engages the rotary valve which is a revolving cylinder. This revolving cylinder has a path which redirects the airflow through additional tubing. Revolving cylinders are common today on modern French Horns.

The significance of the valve was that it could redirect the passage of airflow in a brass instrument from the main tube into several smaller tubes. This could lengthen the instruments and thus change its key. For example, one valve is designed to lower the instrument by one semi tone or half step. This effectively lowers a B flat bugle to the key of A. If a second valve is added, it lowers the instrument by two semi-tones. This effectively changes the B flat bugle by three semi tones or 11/2 steps creating a G bugle. Combining these three valves one can lower the B flat bugle to a G flat, F or E bugle. The use of all three of these valves and their combinations fill in the missing notes in the natural bugle’s overtone series and thus makes it Cornet a Pistons.

Thomas D. Payne was an American inventor who significantly improve the rotary valve. The problem with earlier rotary valves was that they required a great amount of force to operate them. Paine identified the problem and came up with a solution. His ideas was to add another passage through the center of the rotor so that it would only need to turn an eight of the way around rather than the usual quarter turn. This made the valve larger, but Pain was able to reduce the size through further adjusting to the angles at which the tubing entered the valve. His valve systems were used on Cornets by many different manufacturers of that time both domestic and foreign. Payne’s basic system is still in use today on French Horns.

The Cornet a Pistons, or cornet as it is more commonly referred to, became widely implement during the 19th century and particularly popular during the Civil War. This is mostly because it is much easier to play than earlier instruments. Prior to this instrument’s use, high-pitched melodies were primarily performed by the woodwinds. The cornet changed all that. The use of valves made it much easier to play quickly and accurately. It reduced the danger of blunders while performing music in the high range. However, this insurance is at the sacrifice of the brilliant sound that one associates with the trumpet.

One of the reasons that the cornet was more popular for use in brass bands than the trumpet was the mouthpiece. The cornet mouthpiece was deeper and much more flexible than the trumpets. This enabled the members of brass bands to play for many hours at a time without fatiguing their embouchure. The mouthpiece for the cornet during the Civil War was different than the style utilized on cornets today. In the 1860s, cornet mouthpieces were much more conically shaped than those currently in use. They were narrow rimmed, thin walled, with an interior of up to 17 mm in depth. This would gradually taper down. They can be easily compared to a modern French horn mouthpiece. They were usually made of brass or ivory.

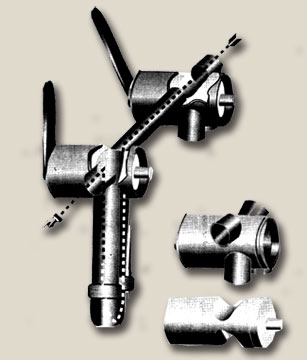

There are several different styles of cornets and they varied from manufacturer to manufacturer, but they wall utilized the same basic principles. The style most popular with bandleaders for the soprano part of a brass band during the Civil War era was the E flat cornet or soprano bugle. It had a length of approximately 3 feet. Another popular style was the B flat cornet, with a length of 4 and a half feet. The B flat cornet played at an octave lower than the E flat and was therefore often used as the Alto voice in a brass band.

The instrument makers of the time used a lead form to shape their creations. Most manufacturers made their instruments out of brass or German Silver. The metal used on instruments in the period of the Civil War was much thinner and more malleable than seen on instruments today. As a result, few cornets have survived from this period.

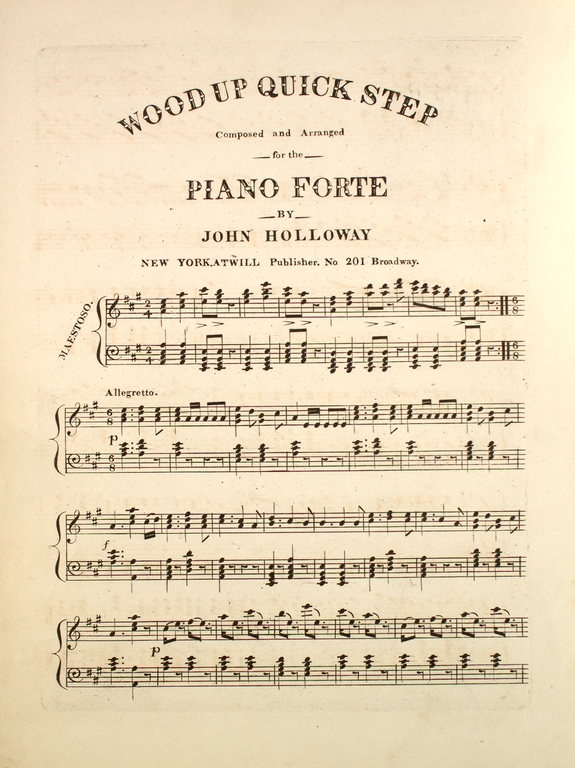

One of the people credited with bringing the cornet to its great popularity during the mid 19th century, is also considered to be the leader of one of the two best Civil War Brass bands in the Union. Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore, a talented cornet soloist and director of the Salem, Massachusetts Brass Band was renowned for his showmanship. In early December of 1856 Gilmore invited the popular keyed bugle virtuoso Edward (Ned) Kendall to perform as a soloist with the Salem band. The two were billed to perform a duel between the keyed bugle and the cornet as they performed the Wood Up Quickstep.

The performance was held in the drill hall of the Mechanic Light Infantry at a cost of 25 cents. The Salem Brass Band, as was the custom of the time, was made up of civilians but was part of the militia company. The only paid member of this sort of ensemble was the leader, in this case the leader was Gilmore.

After he directed a couple of tunes, Gilmore announced Kendall as, “The world’s most famous keyed-bugle soloist.” Kendall then proceeded to solo with the band for three numbers. These have been described in numerous sources as a triumph for Kendal. The performers then broke for intermission. When Ned and Patrick returned, they each sported an E flat version of their respective instruments. They soon began to perform the long anticipated Wood Up Quickstep. It was decided that Mr. Kendal would play the first passage on his keyed bugle and then Mr. Gilmore would answer him by repeating the same passage on the cornet. Both musicians played well. However, the residents of Salem who attended this concert seemed to believe that Gilmore out-played Kendal. This is easy to believe since by today’s standards, the Wood Up Quickstep is a simple piece to perform on a cornet. However, on the keyed bugle it was a whole different story. This performance is considered an example of the decline of the keyed bugle in the United States.

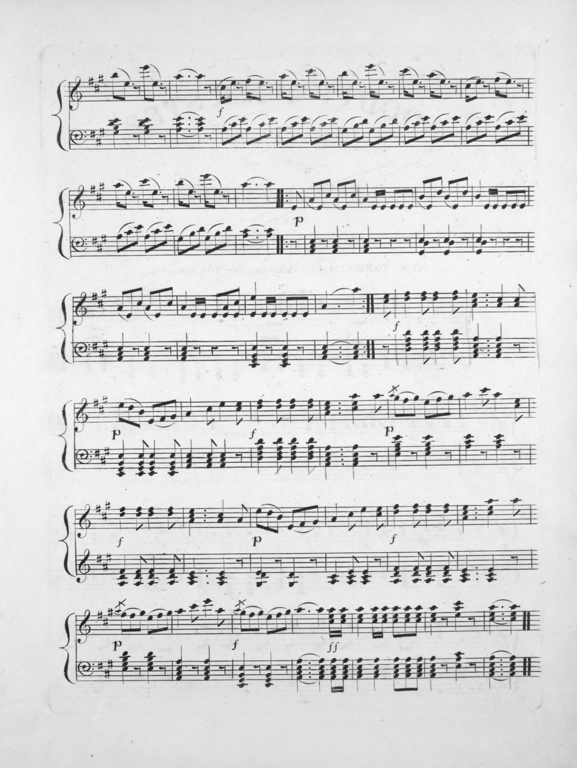

Sheet Music for Wood Up Quick Step written by John Holloway Courtesy of Johns Hopkins University, Levy Sheet Music Collection, Box 161, Item 143

Sheet Music for Wood Up Quick Step written by John Holloway Courtesy of Johns Hopkins University, Levy Sheet Music Collection, Box 161, Item 143

Three months after this vastly documented performance Gilmore won more critical acclaim as director of the Salem band. The Washington Post made special mention of this well disciplined organization. The Post commented on their excellent playing as they performed in James Buchanon’s inauguration parade down Pennsylvania Avenue. The paper commented on the fact that this band managed to stay sober. Most bands of the period drink excessively when on the road (history repeats itself again).

The Salem band was so applauded that they became highly sought after in the Boston area making it next to impossible for the other bands to land a gig. The Salem band’s success struck such a dissonant chord with other Boston area bands, that they decided to take their competition out of the picture. The Boston Brigade Band conspired to attack the Salem Band on the way to a gig in downtown Boston. There was a plan to beat the Salem band’s lips in so badly that they would not be able to play for weeks. The plan also entailed smashing the Salem band’s instruments so terribly that they could never be played again. Gilmore’s notoriety also brought with it many social connections and he was made aware of Boston Brigade Band’s plan. He went to the docks in Salem and found the biggest, toughest crewmen available for hire. When the Boston Brigade Band made their move against the Salem band in the railway station, they were quite surprised to be confronted by brass knuckles, black jacks and belaying pins swung by seamen. They were so surprised that some of the band’s members were unable to run and they received a thrashing.

The Boston Brigade Band finally decided that competing with Gilmore was futile and negotiated a deal which Patrick could not refuse. In this deal, Mr. Gilmore took on all the costs of the band which included music, uniforms, rent and any other expenses which incurred. However, the band was to be known as the Gilmore Band all of its members worked for Patrick. Thus, Mr. Gilmore brought home all of the profits. To ensure the marketability of the band he purchased a great deal of music. He also formed different size and style ensembles so that a group could be provided for any occasion.

As the issues of state’s rights, slavery and finally secession took over public life in Boston, Patrick played patriotic numbers and performed in Fort Warren in The Boston Harbor. These performances were to entertain the glitzy Light Infantry Battalion that was stationed there. The Tigers, as the Light Infantry Battalion were called formed a glee club which sometimes accompanied Gilmore’s band. One of the Tigers favorite tunes was the song John Brown’s Body. This tune is not about Harper’s Ferry, but is significant to the Civil War because Gilmore wrote a popular arrangement for it. New words for this arrangement were later written by Julia Ward Howe, and with these, the tune became the Battle Hymn of the Republic.

As many private bands did during the War Between the States, Gilmore enlisted along with his band. Gilmore’s Band removed the gray uniforms which he supplied and donned the blue style supplied by the Massachusetts 24th Volunteer Regiment in late1861. Two things caused this enlistment. The first was a result of General Order Number 15 issued on May 4th 1861 it called for 39 regiments of volunteer infantry and one cavalry. Musician positions were required for all of these regiments and they included 39 brass bands of 24 bandsmen each. The second was that Patrick Gilmore feared that the ensemble would break up as a result of individual enlistments.

For the most part, the government did not supply these bands with instruments. The required instruments were paid for either by the individual band member or in some cases by the leader of the regiment. It is somewhat surprising then to see that the first proposal for sealed bids for Union army musical equipment included 150 trumpets. It is even more bewildering to know that during the War Between the States, conically bored instruments were much more popular than the cylindrical style trumpet. There probably wasn’t need for more than 20 trumpets in all 39 regiments. Perhaps the military powers simply did not know the difference between a trumpet and cornet.

It can be assured that despite the ignorance in the Union’s top brass, Gilmore’s leadership abilities prepared his band members well for military service. The bandsmen were assigned to General Burnside’s Corps which was already engaged in Virginia. The band spent most of its enlistment traveling the coast in North Carolina. The 24th infantry was very pleased with its luck of having Gilmore’s band assigned to their regiment. One private said, “I don’t know what we should have done without our band. It is acknowledged by everyone to be the best in the division. Every night about sun down Gilmore gives us a splendid concert, playing selections from their operas and some very pretty marches quickstep waltzes and the like. Most which are composed by himself or by Zohler, a member of his band… Thus you see we get a great deal of new music, not withstanding we are off here in the woods.”

During his enlistment, Gilmore’s key solo cornetist was Matthew Arbuckle. Mr. Arbuckle had also achieved fame by dueling with the infamous Edward Kendal. He had previously worked with an American instrument manufacturing company owned by Isaac Fiske. Arbuckle performed in Fiske’s Cornet Band where he, received wide spread critical acclaim.

Despite the immense popularity with troops, the regimental bands became targets for financial pruning by elected officials. In October of 1861 Benjamin F. Larned, Paymaster General responded to Henry Wilson of United States Senate by suggesting that $5,000,000 could be saved annually if regimental bands were taken out of service. In July of 1862, the adjutant general ordered that all bands of the volunteer regiments be mustered from the service, “so much of the aforesaid act… as authorizes each regiment of volunteers in the United States service to have twenty-four musicians for a band… is hereby repealed; and the men composing such bands shall be mustered out of the service within thirty days after the passage of this act.” In August of 1862 the band mustered out. The 24 th Massachusetts regimental commander called their leave, “ a great mistake.”

It is important to note that other regiments were glad to see their bands leave. This only further emphasizes the quality of Patrick Gilmore’s Band. Charles B Hayden of the 2nd Michigan Volunteer Infantry said, “The band has been discharged, right glad we were to be rid of the lazy loafers.”

When the 24th mustered out, Mr. Gilmore went on to support the war effort by performing benefit concerts for a while. However, in 1863, Governor Andrew of Massachusetts requested that Patrick regroup all of the state’s militia bands. He was later inspired by Monsieur Jullien and his large orchestra. Hearing this gave Gilmore the idea of putting on huge scale concerts.

The first of which was in 1864 in celebration of the inauguration of Governor Michael Hahn in “Free and Restored Louisiana.” For this occasion, Gilmore formed a chorus of 5,000 school children. He then organized what was at the time the largest brass band ever. Patrick assembled all of the area regimental bands into a group of 500 instrumentalist and 36 cannons. This included 120 cornets. Around this time, Gilmore also wrote the words and music to When Johnny Comes Marching Home under the pseudonym Louis Lambert.

Gilmore continued to be a prudent businessman. In the late 1860s he formed a partnership with the manufacturer E.G. Wright who supplied many brass instruments during the Civil War. In 1870, Wright, Gilmore and Co. later merged with Samuel Graves and Company to form the Boston Musical Instrument Manufactory.

After the war, the E flat cornet’s popularity was surpassed by that of the B flat cornet. By 1870 though, people’s tastes were changing and the sound of the total brass band was falling out of favor (especially in regards to over the shoulder instruments). In the years prior to the War Between the States, Gilmore]s Band had worked with mixed winds or woodwind and brass ensembles. As the all brass band began to fall out of favor, Gilmore’s band became the post war model for band masters such as John Phillip Sousa and John Duss. On September 24, 1892, Patrick Gilmore passed away. His death took place at approximately the same time as Sousa’s premier, and thus many musical historians feel that Sousa picked up where Gilmore left off.

1 comment

I have a Gilmore Co. SARV Bb cornet made in 1866 when Gilmore ( for a very short time) owned the company in his own right. Anybody know of any other of these very rare cornets?????…….Marty Schmitt